The Second Chalmers Budget

As for the first Budget in October 2022, the macroeconomic backdrop for the Albanese Government’s second budget is an incredibly challenging one. Inflationary pressures – both here in Australia and globally – have proven far more persistent than hoped, although there are now signs that inflation has probably peaked. Central banks across much of the globe – including the Reserve Bank of Australia – have raised official interest rates aggressively, yet the full impact on economic growth has yet to emerge. And while higher commodity prices and strong employment growth have provided a substantial boost to government revenue this year, the budget remains in structural deficit i.e. over the course of an economic cycle, revenue is likely to be insufficient to cover expenditure, particularly given the well-publicised demands on the budget from defence, healthcare and the NDIS.

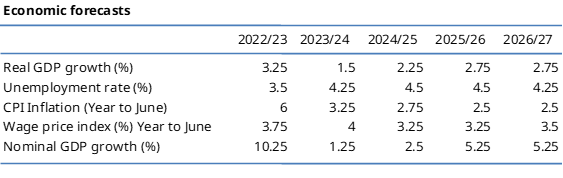

The economic forecasts

Source: Federal Budget 2023-2024

The economy is expected to slow significantly over the next year from growth of 3.25% in the current fiscal year to just 1.5% in 2023/24, before a modest recovery the following year. Inflation returns to the Reserve Bank’s target range in 2024/25. This year, Australia’s nominal GDP growth has benefitted from the sharp rise in commodity prices, a windfall that has clearly boosted revenue (e.g. every $10 increase in the price of iron ore is estimated to boost nominal GDP by around $5.1 billion and tax revenue by around $500 million) but also one that is expected to unwind in 2023/24 and produce a modest gain in nominal GDP. The overall macro forecasts are broadly credible.

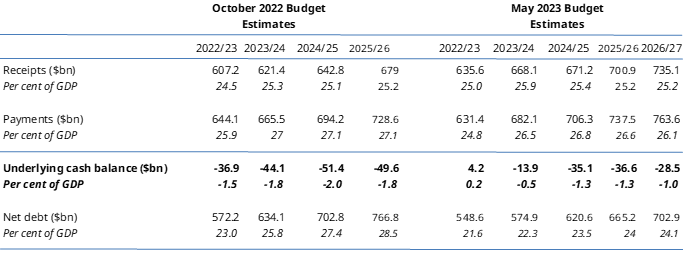

The numbers

Source: Federal Budget 2023-2024

The October 2022 Budget forecast cumulative budget deficits of $235.8 billion for the five-year period from 2022/23 to 2026/27. The cumulative underlying budget deficit is now expected to be $109.9 billion, an improvement of $125.9 billion.

Over the forward estimates, the impact of policy decisions taken by the government since the October budget increases the cumulative budget deficit by $20.6 billion – over half of this (circa $12 billion of around 0.5% of GDP) occurs in 2023/24, with cost-of-living relief accounting for a large chunk of that. The list of measures includes up to $3 billion in energy bill relief for households and small businesses; $1.3 billion for home energy upgrades; a tripling of incentives to encourage greater use of bulk billing. In addition, there’s a (modest) increase of $40 per fortnight in JobSeeker and Youth Allowance payments, a boost to rental assistance payments and an extension of the eligibility for the existing higher rate of JobSeeker payment to single Australians aged 55 to 59 who have been on payment for nine or more continuous months, to match that applying to those aged 60 and over.

The impact of policy changes on the revenue side is relatively limited: changes to the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT) flagged before the budget add only around $2 billion over five years.

The impact of changes to ‘parameters’ i.e the key forecasts for inflation, economic growth, wages and commodity prices - adds $146.5 billion to the bottom line, which allows the Treasurer to state that the government is ‘banking’ the lion’s share of the additional revenue projected to fall into its lap over the next four years.

The economics of it all?

The budget on the face of it is mildly expansionary in 2023-24, and again in 2024/25, but much less so. Over the forward estimates the government can claim to have ‘banked’ circa 85% of the windfall revenue gains. A key question is the extent to which the government’s measures add to demand and hence inflation, making the RBA’s job that much harder. We suspect the answer is “not much” – the magnitude of the stimulus is not that large and the mechanism by which energy price relief is delivered reduced headline inflation through lower energy bills.

What does it mean for how we invest your money?

We’ve indicated in previous post-budget reports that the Federal Budget rarely makes any difference to the way Australian Retirement Trust or indeed any other major superannuation fund invests your money. For the most part, it’s the medium to long term outlook for the Australian and world economies, inflation, interest rates, corporate earnings that are critical in determining what kind of investment returns our members will achieve, not what happens on budget night. And on that score, the May 2023 budget is no different.

This document has been prepared and issued by Australian Retirement Trust Pty Ltd (ABN 88 010 720 840 AFSL No. 228975), the trustee of Australian Retirement Trust (ABN 60 905 115 063) (Fund). This is general information only, so it does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation, or needs. Before acquiring or continuing to hold any financial product, you should consider whether the product is right for you by reading the relevant product disclosure statement (PDS) and also the relevant Target Market Determination (TMD). For a copy of the PDS and TMD visit art.com.au or call 13 11 84.